_________________________________________________________________

Friday, September 21, 2001

Pakistan’s Islamic Colleges Provide the Taliban’s Spiritual Fire

By DANIEL DEL CASTILLO

In the dingy office of Maulana Sami al-Haq, three large, glossy photographs rest on a mantel above his disordered desk — photographs of Mr. al-Haq next to his “good friend” Osama bin Laden.

Maulana Sami al-Haq, the Haqqania's chancellor, confers with a colleague. -photo by Daniel del Castillo for

Mr. al-Haq is the chancellor of Jamia Dar al-Ulum Haqqania — the University of Religious Sciences — or just Haqqania, as it’s more commonly known. Mr. al-Haq benefits politically in Pakistan from his association with Mr. bin Laden and the Taliban government of Afghanistan, who are often viewed as heroes here for standing up to what is perceived as American aggression against the Islamic world.

In 1994, the religious leaders who make up the Taliban emerged out of Haqqania and other madrassas, which are complexes of schools, seminaries, and mosques for the study of the foundations of Islam. Mr. al-Haq boasts that 90 percent of the Taliban’s ruling elite are Haqqania alumni. Taliban ministers, governors, judges, and members of the ruling Supreme Council append the title “Haqqania” to their names, proud of the prestige of their religious training here.

In the 1980s, the madrassas urged their students to go fight the Soviet infidels in Afghanistan. In 1997, Mr. al-Haq closed Haqqania for a while to send the madrassa’s students to help the Taliban take control of Afghanistan from the warlords who were destroying the country.

The madrassas also have enormous political influence in Pakistan. As a member of Pakistan’s parliament in the mid-1980s, Mr. al-Haq pushed through a bill enacting sharia, or Islamic law. The Pakistani government has supported the Taliban, yet tried to limit the domestic power of madrassas and their graduates, fearing that militant Islamic clerics and their supporters might seize political control of the country. Indeed, thousands of madrassa students took to the streets last week to protest the government’s plans to help the United States take military action in Afghanistan, to retaliate for recent terrorist attacks.

Mr. al-Haq and others at Haqqania are proud of having contributed to the formation of political Islam in the region and of their association with the Taliban. “We have supported the Taliban, and we continue to support them. We think they have implemented Islam in its true shape,” Mr. al-Haq says.

Many Islamic scholars disagree with that view. They say that the Taliban leaders have been far better soldiers than they are scholars, and that no support can be found in the Koran for many of their edicts.

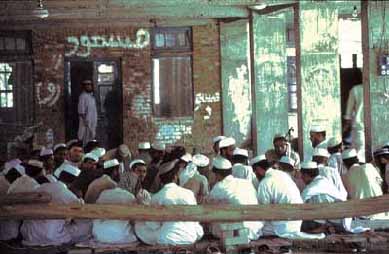

Classroom - Photo by Daniel del Castillo for The Chronicle of Higher Education

Other Islamic scholars also say that Haqqania’s close ties to the Taliban have sometimes been exaggerated. Qibla Ayaz, a professor of Islamic studies at the University of Peshawar, agrees that the majority of the Taliban government has been educated at Haqqania, but says it is not the only madrassa popular with the Taliban. Haqqania’s chancellor, he says, has political ambitions. “Haqqania has come into the limelight, unfortunately, because of Sami al-Haq,” says Mr. Ayaz. “He has claimed very vehemently in the media that Haqqania is the nursery of the Taliban, and now the Taliban are becoming very popular in Pakistan.”

Haqqania is located here in the Northwest Frontier Province, a lawless region of Pakistan ruled by tribal chiefs and smugglers of arms and hashish. For $1.20, foreigners can buy the protection of an armed guard, and most of them do. Haqqania is an hour out of Peshawar, on Grand Trunk Road, a highway lined with Afghan camps, where refugees seek shelter under canvas tarps and sleep on the ground.

The sprawling university complex spans several acres and has an ornately tiled mosque, a 5,000-seat auditorium, and dormitories where students sleep five to a room. No women are visible: In passing, the chancellor mentions a small satellite campus for them.

The majority of the university’s 3,000 students are Pakistani or Afghan, but they are joined by students from Chechnya, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and even China. The university is selective: Just two years ago, Mr. al-Haq says, 15,000 students applied for 400 places. The university survives on the generosity of benefactors, including alumni, Saudis, and other Arabs in the Persian Gulf region. Its willingness to take students who cannot pay for their education — Haqqania does not charge for food, housing, or tuition — has great appeal. “That is why so many students from the Islamic countries want to come here,” says Abdul Qahar, a Pakistani graduate student. “Many students are looking for recommendations and ways to get in here. More than half of my classmates are Afghan.” Afghan students like Haqqania because the language of instruction is Pashto, a language many of them speak.

Although Haqqania confers bachelor’s degrees, master’s degrees, and Ph.D.’s, Mr. al-Haq and his cadre of ulema — religious scholars — teach nothing from the modern era. Their curriculum is based on the Islamic sciences, including distinct disciplines like fiqh (jurisprudence), tafsir (Koranic exegesis), hadith (the sayings of Muhammad), muntiq (logic), and the Arabic language, which is essential to understanding the Koran.

Mr. al-Haq has a beard like his good friend Mr. bin Laden and carries the highest honorific title possible in his Hanafite sect of Islam, Maulana, meaning “master.” He emphasizes that Haqqania is purely an institution of higher learning, that it doesn’t train or arm militants: “We don’t teach cruelty here, we teach them how to resist cruelty.”

Visiting Haqqania is like being transported to a medieval era, with few touches of modern life. The administration uses five computers to publish a monthly religious journal and keep track of its students. Huge electric floor fans circulate the hot, steamy air in the auditorium.

In classrooms, graduate students wearing prayer caps or turbans sit cross-legged on expansive Oriental carpets, caressing their untrimmed beards, as they listen to lectures. Islamic tradition is memorized here, not discussed.

Students say they aren’t bothered by their isolation. “We are religious students, and in an Islamic society there are people who are studying medicine, engineering, and modern technology. They’ll do their jobs, and we’ll do ours,” says Muhammad Hashem, an Afghan student pursuing a master’s degree in Koranic interpretation.

“I know how to drive a car, and I’ve used a computer. What I want to learn, though, is the technology of tanks and munitions,” he adds, implying that he is ready to join the Taliban’s militant wing. Many students and scholars here believe that the United States is against them solely because they are Muslim. “We have our own culture. We want to wear what we wear and do what we do,” says Maulana Rashid al-Haq, the chancellor’s son and the editor of the monthly journal. “Why is that thought of as something rigid? We have not told America what clothes to wear or to grow beards.”

Rashid al-Haq says the relationship between the Taliban and Haqqania began because of the lack of madrassas in Afghanistan. A combination of Marxist rule, the Soviet occupation, and constant civil war over the last 25 years has kept madrassas from taking root in Afghanistan. War has also pushed two million Afghan refugees into Pakistan, and many of them, in dire poverty, have put their sons in the care of the less-selective madrassas.

“The madrassas were basically built to cater to the needs of orphans and the socially deprived,” says an Afghan scholar in Kabul, the capital of Afghanistan, who is studying the Taliban and requests anonymity for fear of reprisals.

He says that in the modern era, madrassas became insular to protect themselves from the cultural threat of colonialism, and have stayed that way. “They did not incorporate the modern sciences, and the gap between worldly knowledge and ‘spiritual knowledge,’ as the mullahs would call it, widened,” he says.

Many Afghan and Pakistani intellectuals say that much of the responsibility for the proliferation of Islamic groups like the Taliban rests with the United States. During the 10-year Soviet occupation of Afghanistan that began in 1979, the United States pumped billions of dollars for arms and military training into Afghanistan and ignored the rise of religious extremism. Much of the American money for training was funneled through the Pakistani military to people who later joined the Taliban.

In 1996, the Taliban began solidifying their power, taking over Kabul for the first time. In 1997, when Haqqania was temporarily closed, the Taliban assumed control of the majority of Afghanistan and imposed a savagely puritanical version of Islamic law that most Islamic scholars say has no basis in the Koran.

The Taliban has issued a litany of repressive edicts, beginning with Decree No. 1, in November 1996, which it awkwardly translated into English: “Women, you should not step outside your residence.” Education for women, from kindergarten on up, was ended, although Kabul University has recently started training some female doctors.

The Taliban also banned kites, dancing, music, television, the Internet, British and American hairstyles, and photographs “of any living thing.” Punishments are severe: 100 lashes for a woman seen with a man who is not her relative.

In a decree issued within the last two months, the Taliban has announced plans to establish 3,000 madrassas in Afghanistan. But given that the government cannot even feed its own people, that edict is being viewed skeptically by outsiders.

Rashid al-Haq supports the Taliban’s plan for new madrassas in Afghanistan. “We’ll be very happy when those are established because we have to turn so many students away here.”

He sees Islam and politics as inseparable, and the Taliban as a successful example of that union. “Had it not been successful, then America and the opposition that wishes to vanquish Islam would not be creating a clamor.”

_________________________________________________________________

Chronicle subscribers can read this article on the Web at this address:

http://chronicle.com/free/2001/09/2001092104n.htm

If you would like to have complete access to The Chronicle’s Web

site, a special subscription offer can be found at:

http://chronicle.com/4free

_________________________________________________________________

You may visit The Chronicle as follows:

* via the World-Wide Web, at http://chronicle.com

* via telnet at chronicle.com

_________________________________________________________________

Copyright 2001 by The Chronicle of Higher Education